|

About Great Lakes Shipwrecks • Shipwreck Map & Index • Great Lakes Scuba Diving • Posters & Photos • Links • Contact |

Cornelia B. Windiate: 1874—1875 Not much is known about the Cornelia B.* Windiate. The small (136 foot long) canal schooner was built in Manitowoc Wisconsin by Windiate and Butler, and named after the builder’s daughter in 1874. The ship went missing in November of 1875 and was felt to have sunk in Lake Michigan because the schooner had not been reported as passing through the Straits of Mackinac at that time. The ship was discovered in May of 1986 by John Steele and Paul Ehorn off Presque Isle in Lake Huron. It is reported that Paul Ehorn was able to immediately identify the wreck by the name carved into the rail on both sides of the rear cabin. The schooner is extremely intact with masts standing upright in about 190 feet of water. The forward mast has a rare yard which would be used to set a square sail below, with a triangular raffee topsail. This rig was a Great Lakes development, evolving the barkentine rig for use with the smaller crews used on the Lakes. The only obvious damage to the wreck is a missing bowsprit, which was damaged in a collision on Lake Michigan earlier in the Windiate’s last trip. The yawl boat is still with the wreck, on the bottom off the starboard side, leading to speculation that the schooner could have become trapped in ice. It is felt that the crew perished attempting to walk to shore over the ice. It is hard to imagine today, in this world where the media keeps tabs on everything from boats setting sail to trends in meditation, that a ship could sail away and never be heard of again. But by the time John Steele and Paul Ehorn solved the mystery of the loss of the Cornelia B. Windiate, all memory of the ship and crew had long passed into history. Please join us on a tour into the past in the video below. *We assumed, as did others, that the “Cornelia” in the ship's name was the builder's wife. Mr. Robert C. Boyles of North Carolina informed us that Mr. Windiate's wife was Cornelia E. Windiate, but they had a daughter they named Cornelia B. Windiate in 1869. We appreciate the correction. Note: Our first dive on the Windiate in 2003 was also a test of an underwater video camera. We had heard that this shipwreck would be well worth a visit, but the experience surpassed all expectations. Standing masts are rare, and so are intact cabins: deck structures tend to to be torn loose by rising air as a vessel sinks. The Windiate still has all the hatch covers in place. It was hard to imagine how slowly and gradually the sinking must have taken place for the ship to land on the bottom in 200 feet of water with everything in place on deck. A close look at the deck in the video reveals lengths of chain stretched out back from the chain locker in the bow. We speculate that with the bowsprit broken off, and the sailors unable to set a foresail to keep the bow up, they attempted to shift the weight of the chains away from the bow. It is also suspected that ice could have formed and sank the ship with added weight, a very real hazard when sailing the Great Lakes in the month of December. A comparison of the video stills (fuzzy, with a scratch on the lens) and the still photos taken two years later reveals the rapid growth of invasive zebra mussels on every surface of this shipwreck. The mussels have greatly improved the water clarity, but our video offers a last good look at the degree of underwater preservation that was practically unique to the Great Lakes.

Jan next to the yard on the forward mast, about 100 feet down.

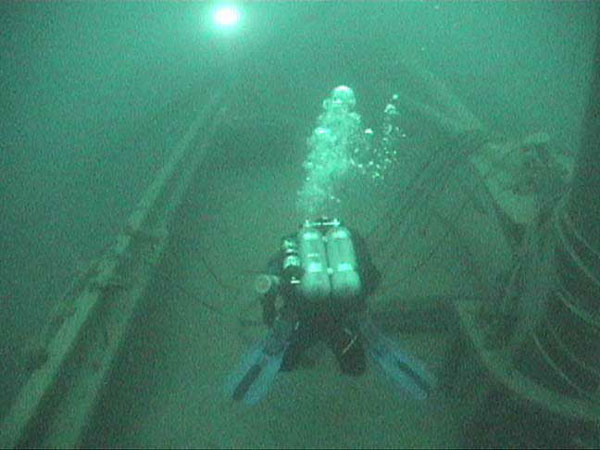

Jeff swims past the middle mast. Note the attached boom and fife rail.

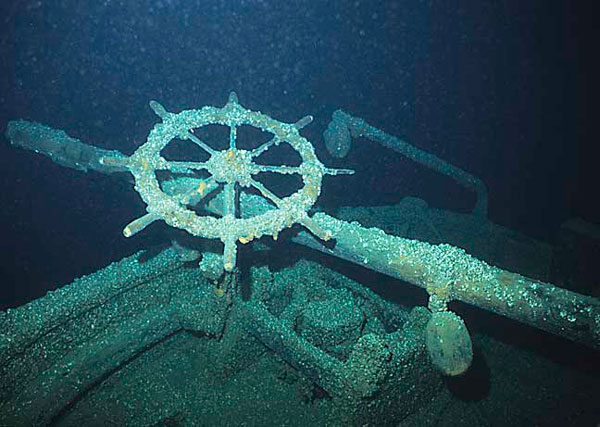

Jan swims over the wheel. The wheel shaft was bent up during an unauthorized attempt to salvage the wheel.

Jeff next to the cabins, aft, port.

This deck box was used for storing provisions. It’s the 19th century equivalent of a cooler.

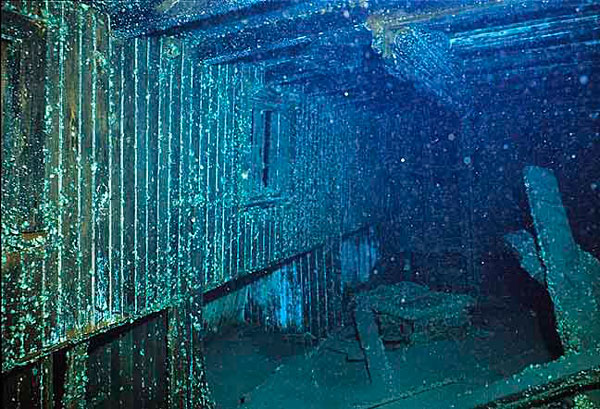

This is inside the cabin at the rear. The square port is in the middle of the photo. The cook stove, half buried in the silt, can be seen at the bottom.

One of the forward masts. The sail appears to have been stowed at the time of sinking, because the boom and gaff are still lashed together. Hoops held the canvas sail, rotted and gone now, to the mast.

This wheel, at the stern, was pulled up and out of position during an illegal salvage attempt. A line was hooked to it and the dive boat, but it did not break free.

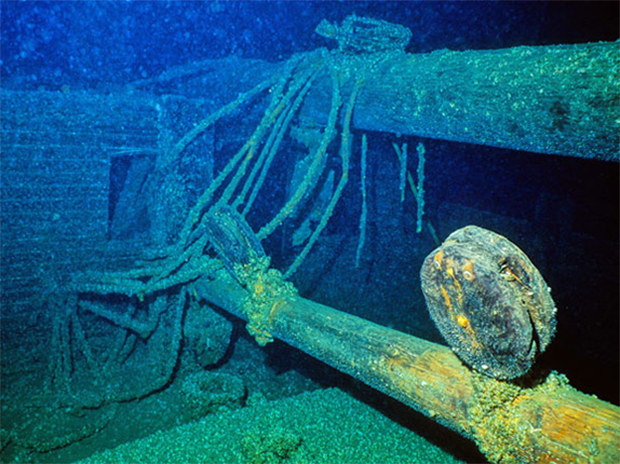

The bowsprit is chained to the front of the wreck. It was damaged earlier, during the same trip, by a collision with another schooner in Lake Michigan. This probably contributed to the schooner foundering in Lake Huron, because they were unable to set forward sails and keep the bow from plunging in a following sea. |

About Great Lakes Shipwrecks • Shipwreck Map & Index • Great Lakes Scuba Diving • Posters & Photos • Links • Contact